Catherine Jacobi | Prof. Jovana Stokic, Ph.D. | Art & Feminism in a Global Context | Spring 2025

British artist Nadia Lee Cohen stands at the crossroads of photography, performance, and fashion, crafting cinematic images that oscillate between dream and nightmare. Her world is not just a stage but a saturated, synthetic mirror of contemporary culture—one where the performance of femininity takes center stage, grotesquely inflated to expose its most absurd dimensions. Cohen’s work blurs reality and artifice, staging hyperreal portraits that critique societal expectations of gender, beauty, and self-presentation.

Through her stylized, hyperreal portraits, Cohen critiques the performance of femininity in mass culture, unsettling beauty norms and exposing the artificial construction of gender identity. Drawing on feminist theorists such as Judith Butler, Laura Mulvey, and Naomi Wolf, alongside Cohen’s own publications Women (2020) and Hello My Name Is (2021), I examine how Cohen’s work negotiates spectacle and objectification, often using parody, self-insertion, and nostalgic aesthetics to illuminate the constructed nature of feminine ideals. Her work engages in a visual dialogue with feminist predecessors like Cindy Sherman and Barbara Kruger, while speaking to contemporary modes of identity performance in the digital era.

II. Aesthetic Universe: The Making of a Visual Language

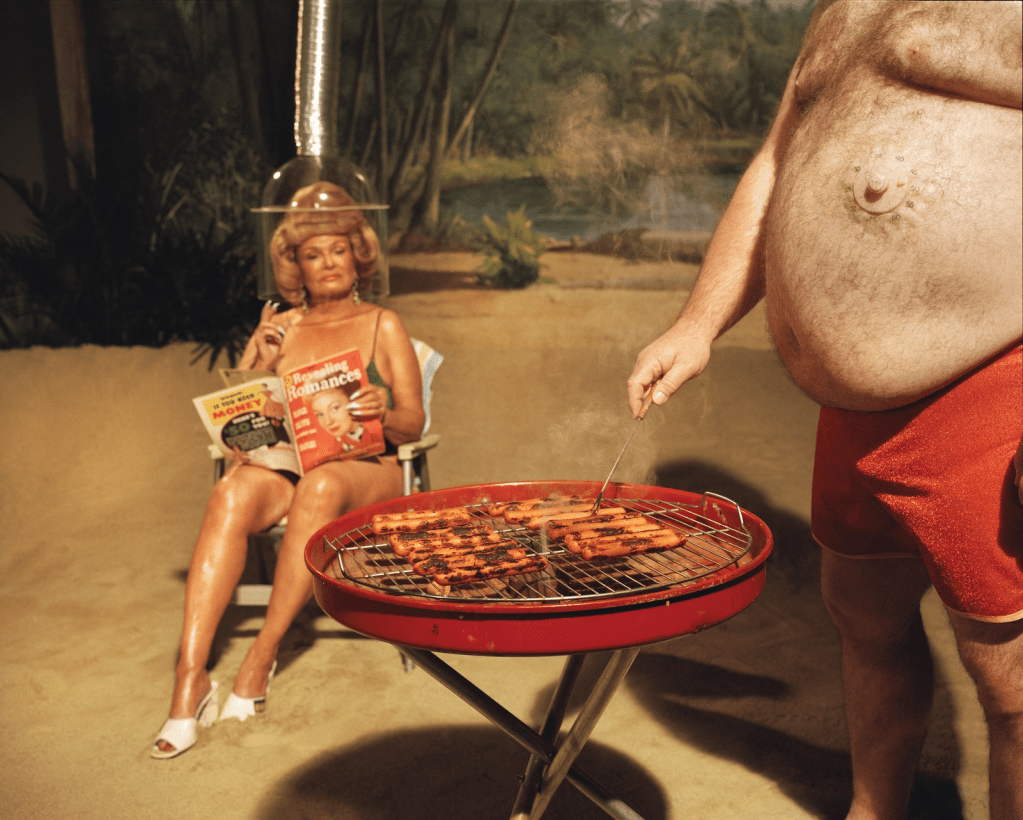

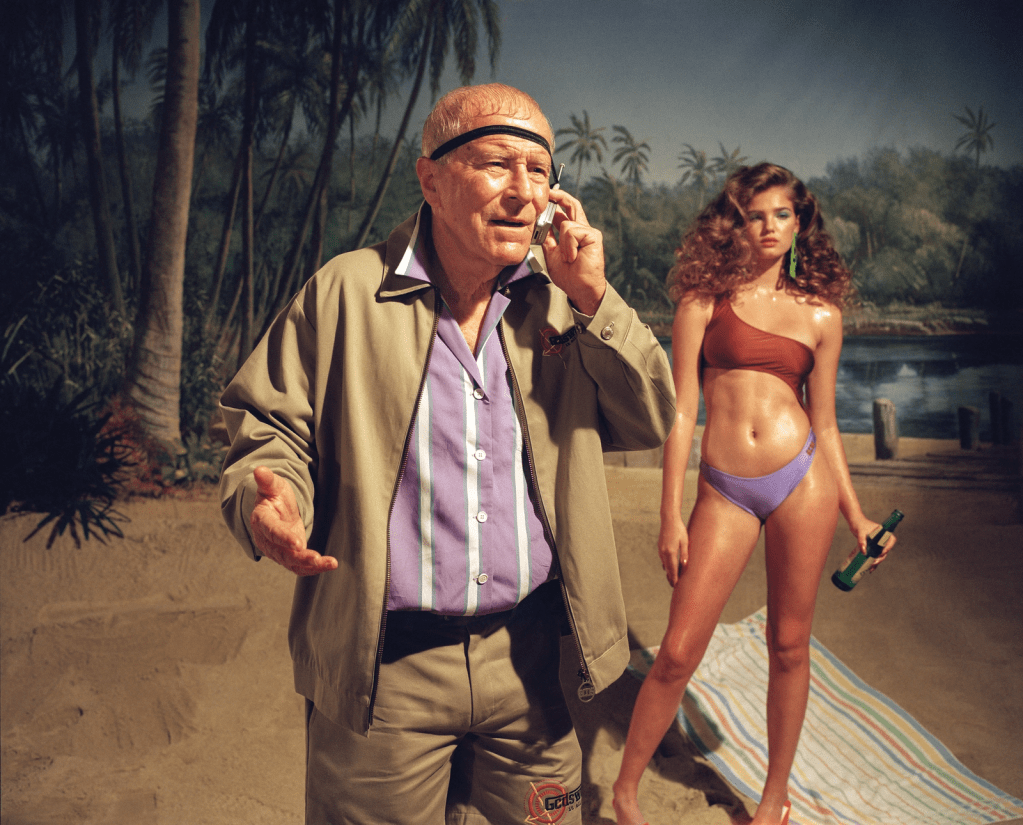

Cohen’s visual language is deeply rooted in the lexicon of Hollywood kitsch, retro Americana, and commercial advertising. Drawing influence from mid-century cinema, pulp magazines, B-movie horror, and the aesthetics of consumerism, Cohen constructs scenes that feel both eerily familiar and theatrically off-kilter. Her photographs are meticulously composed tableaux that evoke both glamour and discomfort; worlds that appear at once desirable and distorted.

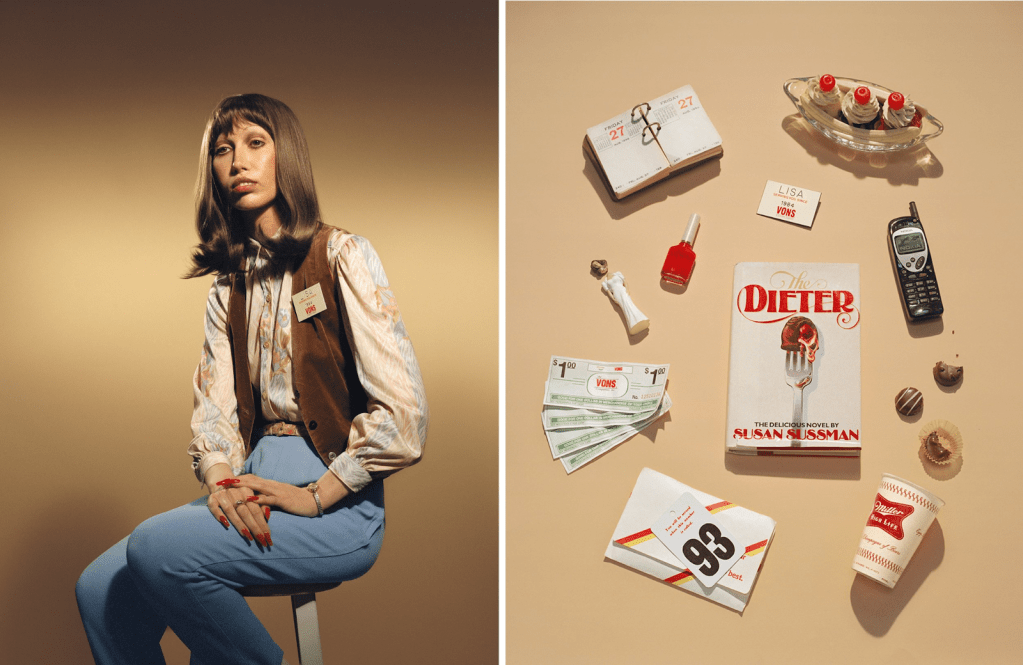

Her book Women (2020) (Cohen, Nadia Lee. Women. Bologna: IDEA, 2020.) presents 100 portraits of women styled with retro hairdos, lacquered nails, bold makeup, and era-specific props. These portraits evoke a stylized version of femininity often consumed via advertising, Playboy magazines, and soap operas. The saturated colors, suburban backdrops, and performative stillness echo cinematic frames frozen in time, while the women themselves appear both empowered and immobilized by the very aesthetic they inhabit. As Alex Tabet notes, Cohen’s imagery reflects “the seduction and absurdity of Americana” while exaggerating its artificiality to the point of satire (Tabet, Alex. “Nadia Lee Cohen’s Characters Confront the Absurdities of American Culture.” i-D, October 6, 2021.).

The artificiality of Cohen’s settings emphasizes that these images are not candid moments, but staged performances. Every detail—be it a neon-lit motel, a plastic-wrapped sandwich, or a pastel-colored rotary phone—functions as a prop in a carefully choreographed fiction. This aesthetic intentionality mirrors John Berger’s observation that “a woman must continually watch herself” in a society where she is both image and viewer (Berger, John. Ways of Seeing. London: Penguin Books, 1972.). Cohen’s images make this double consciousness grotesquely literal.

Nadia Lee Cohen, Women (Paris: IDEA, 2020).

III. Women as Characters: Hyper-Femininity and Parody

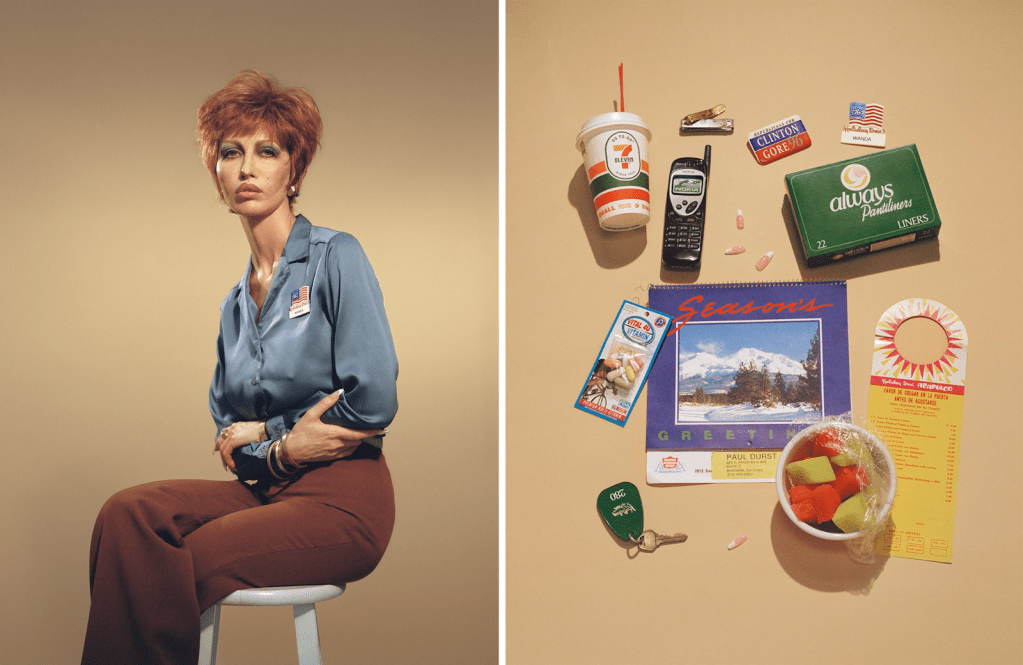

Cohen’s portraits, particularly in Hello My Name Is (2021), consist of her performing invented characters inspired by discarded name tags she found in thrift stores. Each persona is a caricature of a societal role—Marilyn the lonely diner waitress, Trisha the beauty queen, Bernice the coupon-clipping homemaker. These characters do not exist outside the framework of performance; they are simulacra, designed to reflect the absurdity of femininity-as-role.

Nadia Lee Cohen, Hello My Name Is. (Bologna: IDEA, 2021).

Judith Butler’s theory of gender performativity offers a useful lens through which to interpret these images. As Butler argues, “gender is not something one is, it is something one does” (Butler, Judith. Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity. New York: Routledge, 1990.), and in Cohen’s work, gender is clearly done to the extreme. Her characters embody exaggerated, almost cartoonish gender codes, revealing how femininity is constructed through repetition, style, and social expectation.

Nadia Lee Cohen, Hello My Name Is. (Bologna: IDEA, 2021).

The women in Women similarly function as both subjects and objects. Their gazes are often vacant, their poses rigid, their identities flattened into types. But instead of merely replicating this flattening, Cohen stages it with a knowing wink, inviting the viewer to question what lies beneath these façades. This kind of exaggeration calls to mind Laura Mulvey’s notion of “to-be-looked-at-ness” in film, where women serve as objects for male visual pleasure (Mulvey, Laura. “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema.” Screen 16, no. 3 (1975): 6–18.). Cohen’s women appear complicit in this gaze, but also hollowed by it, revealing the emptiness of the roles they inhabit.

Nadia Lee Cohen, Women (Paris: IDEA, 2020).

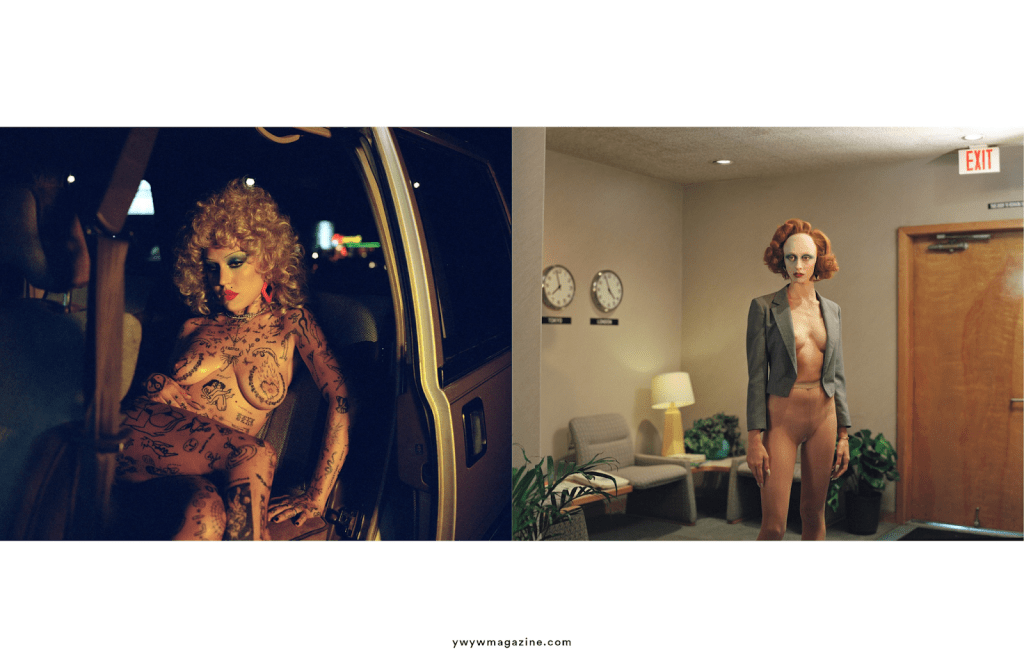

IV. Self as Subject: The Artist Inside the Frame

Perhaps the most provocative aspect of Cohen’s work is her repeated insertion of herself into the frame. By becoming her own subject, she collapses the traditional boundary between photographer and model, artist and muse. Her self-portraits are not expressions of inner truth, but masks she adopts to reflect a broader cultural pathology.

As Antwaun Sargent writes, Cohen’s practice is “as much about constructing a character as it is about reflecting society’s obsession with beauty and identity.” (Sargent, Antwaun. “Nadia Lee Cohen’s Fantastical Self-Portraits.” The New York Times, October 7, 2021.). Her portrayals resist identification with a singular self; instead, Cohen disperses herself into multitudes, a gesture reminiscent of Cindy Sherman’s chameleonic self-portraits. Like Sherman, Cohen does not aim to reveal her “true” identity, but rather to unmask the machinery behind identity itself.

Nadia Lee Cohen photographed by Charlie Denis, 2022 (Above). Cindy Sherman, Untitled #359, 2000 (Below).

This self-performance foregrounds issues of authorship and control. By directing, costuming, and embodying her subjects, Cohen holds creative and visual authority over their representation, disrupting the traditional dynamic of (male) photographer and (female) model. Yet, this authority does not remove her from vulnerability. As Griselda Pollock reminds us, the presence of the female artist in her own work always carries the risk of reinscribing the gaze, even as it attempts to subvert it (Pollock, Griselda. Vision and Difference: Feminism, Femininity and the Histories of Art. London: Routledge, 1988.). In this way, Cohen’s self-portraits oscillate between agency and exposure.

V. Feminism, Spectacle, and the Gaze

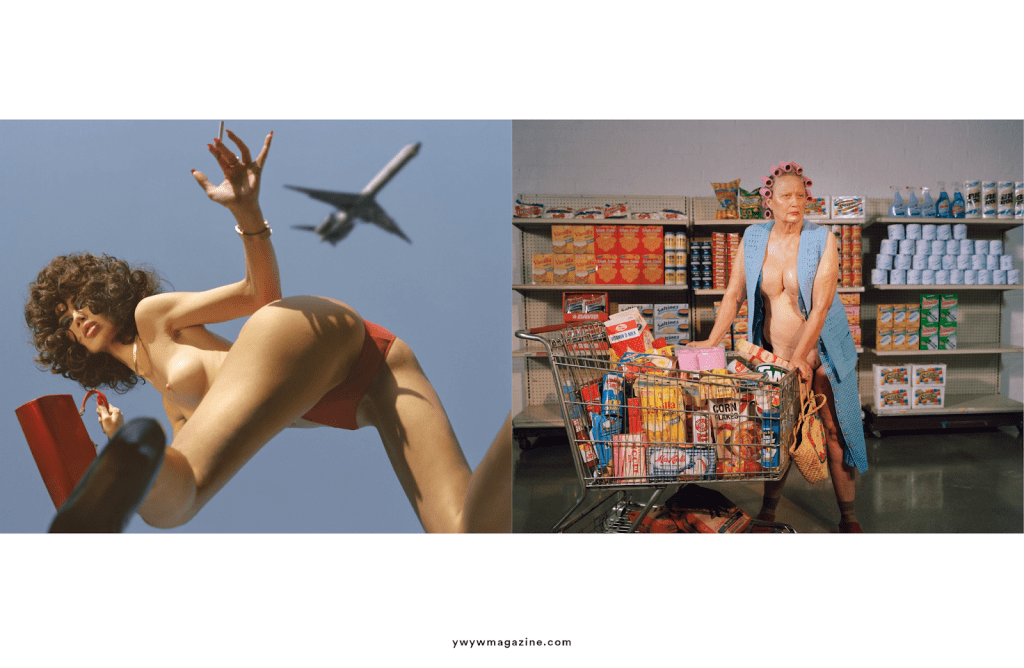

Cohen’s relationship to the male gaze is fraught and complex. On one hand, her work appears to embrace spectacle—her images are undeniably glamorous, fetishistic, and heavily styled. On the other, her over-the-top aesthetic functions as a form of parody that destabilizes the viewer’s pleasure.

Nadia Lee Cohen, Future Beach, 2019.

Drawing again on Mulvey, the notion of “visual pleasure” becomes central here. Cohen seduces the viewer through surface beauty, but simultaneously undermines that pleasure by inserting signs of discomfort—blood, smeared lipstick, deadpan stares. Her characters rarely smile. Their expressions are often blank, ironic, or subtly antagonistic. This tension is the critical space of Cohen’s feminism: she lures the gaze only to expose its violence.

Nadia Lee Cohen, Future Beach, 2019.

Her work aligns with Naomi Wolf’s The Beauty Myth, which critiques the ways in which beauty standards are used to discipline women (Wolf, Naomi. The Beauty Myth: How Images of Beauty Are Used Against Women. New York: Harper Perennial, 1991.). Cohen’s women appear to have internalized these standards to grotesque extremes, becoming parodies of themselves. This critique is embedded in the hyper-commercial styling of her photographs: by mimicking the visual codes of fashion, film, and pornography, she questions their power.

Nadia Lee Cohen, Future Beach, 2019.

Comparisons to feminist predecessors like Barbara Kruger are useful here. While Kruger uses text to subvert visual culture (“Your Body is a Battleground”), Cohen uses theatricality and costume to achieve similar ends. Both artists expose the social scripts that define femininity, though Cohen does so through immersive fiction rather than direct address. I find myself particularly interested in her work because of these unnerving visuals. The more I look at any of Cohen’s work, the more disconnected I feel from reality itself, and the closer I am to her mind.

Nadia Lee Cohen, Future Beach, 2019.

VI. Critiques and Complications

Cohen’s work is not without its critics. Some argue that her images are too stylized to be truly critical—that they indulge in the very aesthetics they claim to subvert. In the i-D article by Tabet, this tension is acknowledged: “her work walks a tightrope between fetish and satire, celebration and critique.” (Tabet, Alex. “Nadia Lee Cohen’s Characters Confront the Absurdities of American Culture.” i-D, October 6, 2021.). This ambiguity raises questions about audience interpretation. Is the viewer in on the joke, or seduced by the surface?

Bella Hadid photographed by Nadia Lee Cohen for Balenciaga, 2022.

Moreover, Cohen’s collaborations with high-end fashion brands like Balenciaga, Gucci, and Skims complicate her feminist critique. When her aesthetics are used to sell luxury products, do they lose their edge? Or can commercial platforms be vehicles for feminist disruption? This tension echoes debates around postfeminism and the commodification of empowerment—where feminist language and imagery are absorbed into marketing strategies that ultimately reinforce consumerism.

Yet, perhaps Cohen’s ambivalence is the point. In today’s media landscape—dominated by influencer culture, TikTok identities, and curated personae—feminist critique must grapple with irony, spectacle, and the blurred boundaries between authenticity and artifice. Cohen’s work reflects this cultural terrain with uncanny accuracy.

Kim Kardashian photographed by Nadia Lee Cohen for Skims, 2022.

VII. Conclusion

Nadia Lee Cohen’s photography operates at the intersection of performance, critique, and seduction. Through her hyperreal aesthetic, she constructs a feminist visual language that exposes the artificiality of gender roles, interrogates the spectacle of femininity, and reclaims agency through parody and self-representation. Her images are unsettling because they hold a mirror to the grotesque beauty of mass culture, revealing the labor behind every “natural” pose.

By occupying both the role of subject and creator, Cohen disrupts traditional modes of authorship and control, staging herself as a feminist provocateur in a glossy, media-saturated world. While critiques about the commercial entanglements of her work are valid, they also reflect the complexities of contemporary feminist art practice—where resistance and complicity are often intertwined.

In placing herself and her characters within carefully constructed fictions, Cohen reminds us that identity is always a performance—and that power can be found in both embodying and exploding the script.

VIII. Personal Reflection: A Seductive Critique

Encountering Nadia Lee Cohen’s work for the first time felt like entering a surreal dreamscape; one tinted in plastic, lipstick, and longing. Her images are undeniably seductive. The richness of color, the precision of composition, the theatrical costuming, they draw the eye in with cinematic allure. But this is precisely what makes her work so unsettling. Her women do not invite empathy or even narrative identification; they confront, dazzle, and disturb in equal measure.

As a viewer socialized in a media-saturated culture of beauty ideals, I find Cohen’s exaggerations both thrilling and disorienting. On one level, I admire the control and intentionality she wields in constructing every detail of her scenes. Her work is empowering in the way it wrests authorship away from the traditional male gaze, placing the woman—often herself; at the center of authorship and vision. Yet, on another level, I remain cautious. The beauty of her images is sometimes so overwhelming that the critique risks being subsumed by the spectacle.

There is a fine line between parody and perpetuation. While Cohen clearly intends to expose the absurdity of gender performance, there are moments when her work teeters into fetishization, particularly when consumed through fashion platforms or social media, where ironic distance can easily be lost. Still, I believe this ambiguity is what gives her work potency. It doesn’t offer easy answers or moral clarity. Instead, it stages discomfort, posing critical questions about how we look, why we look, and who controls the frame.

Ultimately, Cohen’s work succeeds in challenging the boundaries between art and performance, subject and object, empowerment and exposure. It forces us to confront the roles we play in consuming images of femininity, and to ask whether we are ever truly outside the spectacle ourselves.

Bibliography

Berger, John. Ways of Seeing. London: Penguin Books, 1972.

Butler, Judith. Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity. New York: Routledge, 1990.

Cohen, Nadia Lee. Women. Bologna: IDEA, 2020.

Cohen, Nadia Lee. Hello My Name Is. Bologna: IDEA, 2021.

Mulvey, Laura. “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema.” Screen 16, no. 3 (1975): 6–18.

Pollock, Griselda. Vision and Difference: Feminism, Femininity and the Histories of Art. London: Routledge, 1988.

Sargent, Antwaun. “Nadia Lee Cohen’s Fantastical Self-Portraits.” The New York Times, October 7, 2021. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/10/07/arts/design/nadia-lee-cohen.html.

Tabet, Alex. “Nadia Lee Cohen’s Characters Confront the Absurdities of American Culture.” i-D, October 6, 2021. https://i-d.vice.com/en/article/7k8pjy/nadia-lee-cohen-hello-my-name-is-book.Wolf, Naomi. The Beauty Myth: How Images of Beauty Are Used Against Women. New York: Harper Perennial, 1991.

Leave a comment